The regimen that would come to define Mookie Betts’ offseason began with a photo.

The six-time Gold Glove Award-winning outfielder didn’t want to waste any time as he prepared for a full-time move to shortstop. In order to make his second attempt at the Herculean task a success, he first had to find somewhere to practice. With Dodger Stadium undergoing renovations, that meant getting creative.

Just weeks after winning the World Series, Betts began working out at Crespi Carmelite High School, not far from his home in Encino. By chance, Dodgers video coordinator Petie Montero happened to recognize the location after Betts took a picture with a group of kids he used to coach.

So Montero reached out, reminding Betts that he lived close by if he wanted an extra hand.

“Can you come tomorrow?” Betts replied.

In the middle of November, Montero reported for duty with his fungo bat and his iPad, ready to send video of Betts’ workouts to new infield coach Chris Woodward. Thus began what would become a near-daily occurrence as Betts assembled a task of helpers to prepare for a switch that few big leaguers, let alone an eight-time All-Star outfielder, would dare to make at 32 years old.

“I think the most exciting thing is just to prove everybody wrong,” Betts said this spring. “All the people that doubt me, they’ll see.”

Betts’ newfound confidence at the position stemmed from his preparedness.

While a few months of work can hardly compare to the experience most major league shortstops have at the position, it represented an eternity in contrast to the 12 days of notice Betts received last season when he first attempted to make the switch. In 2024, Betts was named the everyday shortstop on March 8, less than two weeks before the Dodgers opened their season in Korea. Plans to have Betts play second base changed when throwing issues plagued shortstop Gavin Lux in the spring, compelling the Dodgers to change course.

The opportunity exhilarated Betts, who came up through the minor-league ranks as a middle infielder but hadn’t played shortstop regularly since high school. When he logged his first big-league inning at the position in 2023, he called it a “dream come true.” Getting sporadic playing time at the spot, however, did not compare to the rigors of manning the position full time at the start of last season.

Betts spent hours before every game taking grounder after grounder in an effort to survive at one of the most demanding positions in the sport. He reviewed film with Miguel Rojas, absorbing tips about the fundamentals from the veteran. He watched YouTube videos of the best shortstops every night, hoping to open his mind to what was possible. He would go to sleep playing out different scenarios in his head: Seventh inning, one out, man at third, backhand play.

It was exhausting.

“The challenge is fun and I embrace it,” Betts said, “but it does keep you up at night.”

RELATED: Ranking the 10 best shortstops in MLB for 2025

Betts played the position commendably, all things considered, but he committed nine errors in 65 games and did not grade out favorably by most defensive metrics. In a self-evaluation last May, he described his performance as “not very good.”

And yet, behind an extraordinary offensive skill set, he was still one of MLB’s most valuable shortstops by wins above replacement before fracturing his hand in June. The injury would mark the end of his tenure as the Dodgers’ shortstop.

At least for the 2024 season.

After two months off, Betts and the Dodgers’ staff looked at the roster and came to the conclusion he would be best suited in right field for the stretch run. Betts conceded at the time that the move gave the Dodgers the best chance to win. Those close to him, however, knew better than to think he had permanently surrendered the dream.

“He looked at me, and he goes, ‘It ain’t over yet,'” Woodward recalled.

At the time, Woodward was serving in a senior advisor role. After the Dodgers won the World Series, Woodward took over as the club’s infield and first-base coach in November. Before he had even considered the role, he already knew that Betts intended to make the switch to shortstop and had the confidence and blessing of the front office. The Dodgers believed Betts was capable of correcting the issues that plagued him.

‘All the most challenging parts of the position, he does really well,” Dodgers general manager Brandon Gomes said. “Where he struggled was throwing. You go watch him in right field, it’s one of the best arms in the game. It’s incredibly accurate. Those things that are most challenging to teach — getting off the ball, range, making exceptional plays, his pre-pitch timing — he nailed those.”

The arm strength Betts displayed in the outfield hadn’t translated to the infield. More glaringly, eight of the nine errors he committed at shortstop had occurred on throws.

“We kind of forced him into it on the fly last March,” Dodgers president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman said. “And his point is, ‘If I have an offseason to train for this and to get my body in those position and to learn this, I have no doubt that I can figure it out.'”

So, the Dodgers gave him that chance.

They spent a fortune both acquiring and retaining stars on the pitching staff and in the outfield in an effort to defend their championship title, but they didn’t sign a replacement at shortstop. Betts would get the opportunity to solidify the spot.

“He is dead set on it,” Friedman said this winter. “He is very confident about it, and I will happily take the side of betting on Mookie, unlike any fool that wants to take the other side.”

Betts’ preparation would take him on an informal tour of high school and college infields throughout the San Fernando Valley, from Crespi to Sierra Canyon High School to Los Angeles Valley College. When wildfires decimated parts of Southern California in January, the workouts shifted to Loyola High School, which ended up offering one of the better infields. The work began slowly, starting with fundamentals.

“We’re going to do this until you get bored,” Montero would tell Betts during the first month of work. “You have to master this.'”

Montero hit fungos to Betts from the edge of the infield grass and worked in fives — five right at him, five to his forehand, five to his backhand — before backing up 10 feet and doing it again. At first, Betts would just catch and hold the ball. Then he progressed to moving his feet. Then to short throws. Then he put everything together.

The workouts would often last three to four hours per day, three days per week. Soon, they picked up to four times a week. Then five. Then six. Those who watched noticed a visible difference in his throws from the season prior.

“Night and day,” Woodward said.

Every shortstop has his own style, Woodward explained, and he did not want to force Betts to play a certain way. Rather, he hoped Betts could find an approach that would feature his athleticism.

“Carlos Correa never fields a ball with two hands,” Woodward said. “Every ball is to the side. The old traditional guy would be like, ‘What are you doing? You gotta get in front of the ball.’ OK, tell Carlos Correa that. He’s a platinum, Gold Glove guy.”

A similar style had worked for Corey Seager, whom Woodward coached both in Los Angeles and Texas.

As it turned out, it felt right for Betts, too.

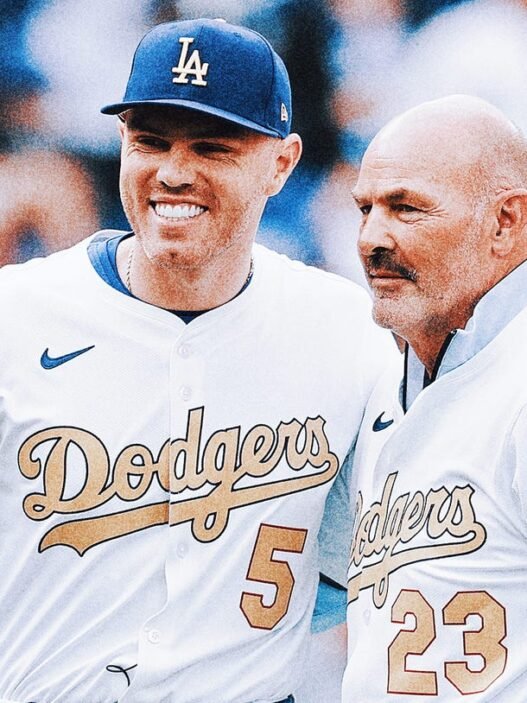

Betts found a foundation through collaboration, not only with Woodward and Montero but also with Angels infield coach Ryan Goins, who’s one of Betts’ best friends, and five-time All-Star shortstop Troy Tulowitzki, whom Betts traveled to Texas to visit with for a few days. Tulowitzki operated with a downhill approach that resonated with Betts, who now feels more comfortable throwing the ball on the run.

“Mookie loves to play more free, a lot of one hand, but he’s added a lot of elements that aren’t exactly that,” Woodward said. “So, he can go two hands, he can go stationary, he can go more traditional when he needs to. Now, he’s actually not thinking about stuff out there.”

Nailing down those consistent mechanics became crucial, especially with the setback that occurred over the past couple weeks. If making the switch to shortstop wasn’t difficult enough, Betts will now be doing it in a much lighter frame than the 175 pounds he reported to camp weighing.

He began feeling ill two days before the Dodgers departed for the season-opening Tokyo Series. The plane ride was brutal. He tried to fight through an undiagnosed stomach issue, but the sickness was unrelenting. His fatigue was obvious when he took ground balls before the Dodgers’ exhibition games in Japan.

“Every other rep was, like, out of gas,” Woodward recalled. “He couldn’t stay in his legs consistently. One rep was really good, and you could tell it took a lot out of him, and the next rep wasn’t great.”

Betts didn’t play in the Dodgers’ games against the Cubs in Tokyo on March 18 and 19. He received intravenous fluids and was sent home early. A week after the Tokyo Series, he still couldn’t keep solid food down. At one point, he had lost nearly 20 pounds. But his vitals and bloodwork came back clean, and he was still able to work out. He said felt fine — until he tried to eat.

He was scratched Sunday from the first game of the Dodgers’ Freeway Series matchup against the Angels after throwing up again and was at a loss to explain what was going on. The illness had lasted two weeks.

“It was getting to be pretty concerning,” manager Dave Roberts said, “because there really isn’t something to kind of compare what he’s going through.”

With only days left until the home opener, Roberts said there was consideration of shutting Betts down to get his weight and strength back up.

But on Monday, Betts turned a corner.

He got through a full workout at Dodger Stadium and, more importantly, finally kept food down. Though still much lighter than usual, he began to pack on some of the lost weight. On Tuesday, Betts returned to action for the spring finale, getting three at-bats and manning shortstop.

At that point, there was no question in his mind about his availability for Thursday’s domestic Opening Day.

“Once I step foot on the dirt, I’m ready to go,” Betts said.

While it’s hard to know how Betts will be feeling physically, Woodward is confident that Betts has developed enough consistency with his mechanics that the layoff won’t doom him. That’s the result of the collective work Betts and his advisors put in this winter.

Throughout the offseason in Los Angeles, Montero would send video of Betts’ workouts to Woordward in Arizona and AirDrop a copy to Betts to analyze. There were daily check-ins and conversations. When the workouts ended, Betts usually sought immediate feedback.

“It was a running joke in the household, ‘When’s Mookie going to call?'” Woodward quipped.

There were times when the group decided to take a day off, only for Betts to request a workout anyway. Often, Betts would self-critique something he saw on video and already know what he wanted to work on the following day.

In January, he was flying back from a baseball clinic he hosted for kids in Japan when he shot a message to the group.

“It might have been 11 o’clock or midnight, and I was still up,'” Montero recalled. “He goes, ‘Hey, boys, I want to get some work in. I’II fly in, I get in at 10.’ Like, what are you going to say? Yeah.”

“It takes an obsession, a lack of balance in your life, maybe, to just overcommit to something and say, ‘F— this, I’m going to be the best in the world at this,'” Woodward added. “That’s him in a nutshell.”

Goins developed a close friendship with Betts when the two were American League East division rivals for four seasons. The former Blue Jays shortstop would often ask Betts questions about hitting. This winter, the roles were reversed for the longtime offseason golfing buddies.

Goins let Betts know he was there for him if he had any questions about fielding the position. He figures Betts will be athletic enough to handle the transition, though there are obvious challenges for anyone trying to do what Betts is doing.

“The biggest thing is the ball’s just on top of you faster than in the outfield,” Goins said. “Your first step needs to be better. Outfield, you can kind of watch the ball go up, and the first step will matter, but it’s just way more important in the infield. A lot more going on with baserunners. All of it. The game just moves a little faster in the infield.”

Similarly, veteran shortstop Kevin Newman, who played in the N.L. West with the Diamondbacks last year and is now on the Angels, said he thought the two most difficult aspects of the move would be finding and reading the hop and managing the internal clock.

“I don’t know him off the field, but I know he bowls a 300 and dunks and can throw a pigskin wherever he wants it,” Newman said when Betts was first attempting the move last season. “I know he’s an incredible athlete, so just thinking, if anybody can do it, it’s probably him.”

Still, those aspects of playing the position can really only be learned through experience and repetition, as Betts learned.

“At first I was not good, when I first started in November,” Betts said. “Still had a throwing problem. Still wasn’t fielding it right. And I gave myself grace. My wife actually was the one that told me, give myself grace, be patient with yourself. I just stuck with it. I stuck with the process over and over again.”

Often, when Betts was fielding on the run last year, he would try to get rid of the ball too fast. The Dodgers tried to reinforce the idea to him that he has more time than he thinks. Montero brought a stopwatch to the workouts this offseason to time Betts’ throws. Sometimes, he would run down the line after hitting a grounder just to give Betts a more realistic look.

Footwork was always a focus at the workouts. In the past, Betts was prone to throwing flat-footed too often. The Dodgers wanted to get him in a place where he was catching the ball with as much momentum moving forward toward the base he was throwing to as possible. He developed a routine for throwing on the run and for throwing off one leg.

The uncertainty and restlessness that Betts felt last season have dissipated. He has a much better feel now for the types of throws he has to make and the technique required to make them.

“Now, he’s just in a much better place,” Woodward said. “He can sleep at night.”

That doesn’t make what Betts is attempting to do any easier.

If it doesn’t work out, the Dodgers have contingency options in Rojas, Tommy Edman, Kiké Hernández and Hyeseong Kim.

But Betts is not thinking about a fallback plan. He feels ready to turn the doubters into believers.

“I don’t know what to expect, I just know I believe in myself,” Betts said last month. “I believe in all the hard work I’ve put in, and I think it’ll show.”

Rowan Kavner is an MLB writer for FOX Sports. He previously covered the L.A. Dodgers, LA Clippers and Dallas Cowboys. An LSU grad, Rowan was born in California, grew up in Texas, then moved back to the West Coast in 2014. Follow him on X at @RowanKavner.

Get more from Major League Baseball Follow your favorites to get information about games, news and more